Pam’s Pictorama Post: I continue to work my way through the available books by Mrs. George (nee Jessie Mansergh) de Horne Vaizey, as chronicled in early parts here and here. I have had a tough time reading with a consistent timeline so I have hopped a bit through her ten year, prolific career and have been spending a lot of time around 1908 and 1909 recently, with a few jumps to near the end of her life in 1917.

There is not a lot of deep biographical information readily available and I sketched out most of it in my second post about her. She had a good for nothing drug addicted husband who had the good grace to die and she starts publishing shortly after. What I didn’t know until recently was that her young daughter, Gwenyth, took one of her stories from a drawer and sent it to a magazine contest without telling her mother. Jessie won and the prize was a cruise where she met George de Horne Vaizey and they marry and meanwhile her career was launched.

So the question of what was really lighting a fire under her about writing is an open one – she must have enjoyed it, but was it a financial need? I always thought she wrote for a longer time before remarrying and needed to support her family. Nonetheless, write she does with tremendous output. Wikipedia counts 31 books in the span of her brief career (another site says 33) and I think we have to assume there were magazine stories published as well. (There appears to be a collection of them published either right before or after her death.)

Her books are not especially brief. I would say they average around 300 pages. Reading them electronically it is a bit hard to tell. Sometimes two or even three were published in a given year.

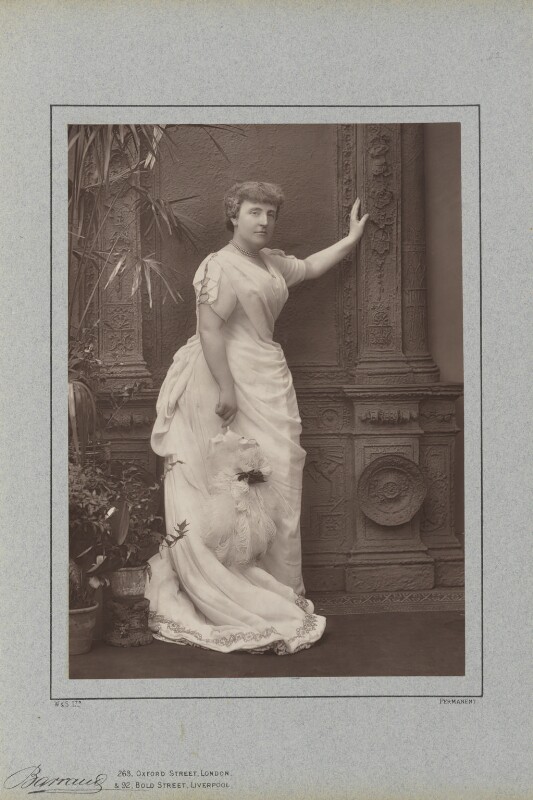

I have been thinking about her heroines as I read and as they grow in interest with her increased skill as a writer. They stop being simply likable (beautiful and loveable – gray eyes, long lashes) fairly early on and start to become more complicated. In Flaming June (note that the painting above is of the same name and was well known at the time – was she making reference to it? Frederic Leighton, 1895 – I say yes!) she has an American main character with a Western accent which, while effective, gets a bit tedious to read after awhile. (She also had a character with a lisp in one volume that started to drive me nuts. It seems to be a fashion for writers of the time to show all the accents they could write with.)

However, over time her women grow into complex characters who are sometimes more interesting than likeable. For example, the woman in Flaming June is hot tempered and extremely independent. Much of the plot, and what happens to her both good and bad, centers on this quality as well as her stubbornness. It makes the story tick and, without being a spoiler I will say, gives it a somewhat quixotic ending.

In addition to greater character development her plots become more interesting and she leaves off the basic sort of worn tropes about school days and money acquired, lost and acquired again which were the bread and butter of her early writing and certainly for women authors of the day. A young woman of middling income decides to take a basement flat in the city and dress as a much older woman so that she will be free to help people in a way that an attractive young woman could not. (The eponymous volume is The Lady of the Basement Flat, 1917.) The story is worked however so that she also has a life at a country house where she is herself – of course the two weave together at some point. However, what a concept!

In What a Man Wills she takes a sort of well trod narrative path with a wealthy, ill, elderly man who invites four nieces and nephews for a long visit to decide who will be his heir. While, again without being a spoiler, I would say she doesn’t manage an entirely new take on it, she does well with expanding it and again, not afraid to make one of her main characters flawed.

Her women, even her heroines, can fall victim to vanity and greed, if not quite all the way to ambition. (She does poke fun at women authors occasionally with a sort of self-deprecation.) They are often a bit forward for the time and space they live in – especially those who reside in or come to find themselves in small rural towns. Financial ruin comes to people and families on a routine basis, but with a sort of detail that makes you think that for those who lived on investment income they way many people did at the time, that this was a very real event.

Her characters opine on the limited options for women – that they are not trained for anything to prepare them for life or possible ways to make a living. Therefore their fortunes hang largely on their ability to marry well – or remain dependent on a male relative or someone else to settle money on them. In the end this depends on how attractive they are and can make themselves and some of the more forward characters have a real struggle with this very real problem.

Frankly, the male characters tend to be a bit more one dimensional; she came from a large family and almost all of her characters do. Therefore, there are always a few brothers for color and plot development and of course there are suitors, and although we are privy to fewer of their thoughts and motivations, they are generally not fleshed out like the women are having they were often an end goal which offered security and a home in addition to whatever romantic interest was brought to the table.

The closest we come to the male prospective in the somewhat brilliant novel, An Unknown Lover. This is a complicated plot and while there is a woman at the center of it, we do get into the heads of both her epistolatory lover and brother and their motivations which help drive this story. Thus far I would say this is her best, published in ’13 so she is flexing her muscles, but not yet at the end of her life.

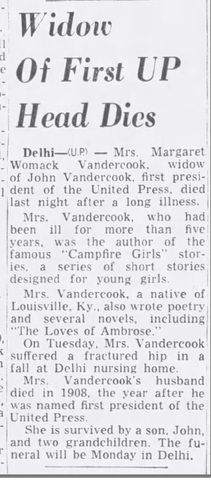

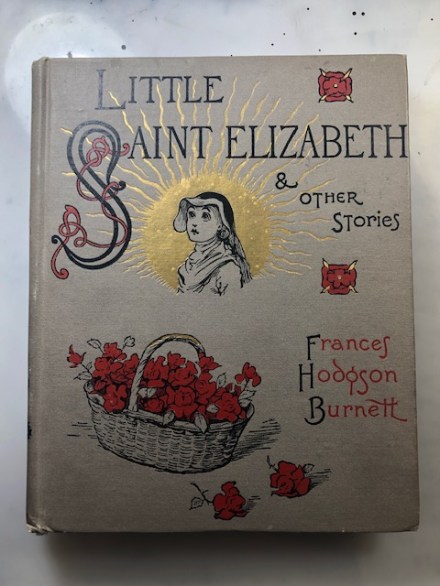

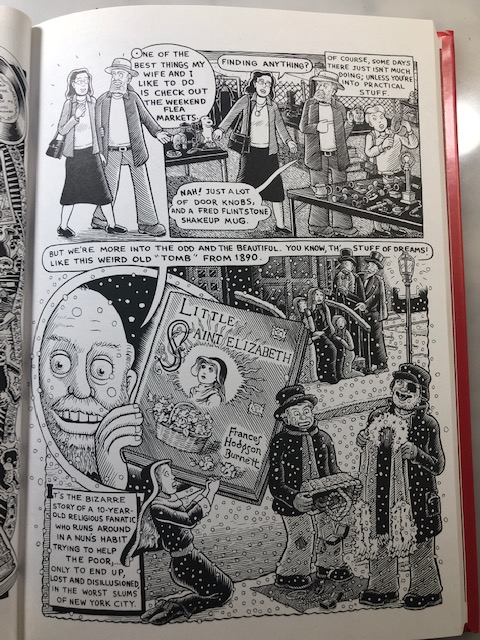

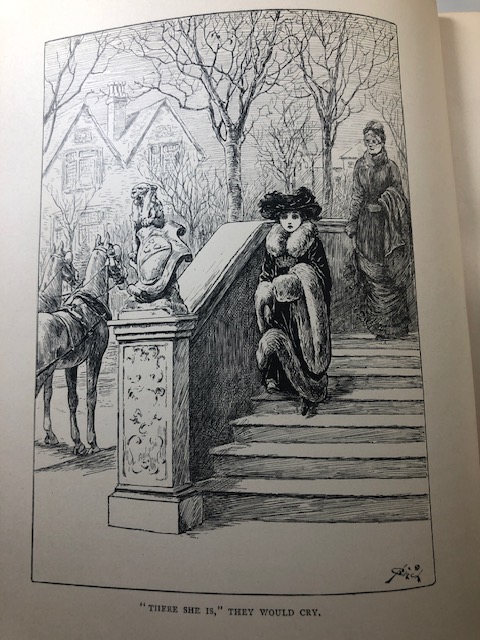

So my interest in women authors at the turn of the last century continues unabated. Watching them chafe at the conventions that defined their lives and dictated how they could live – sometimes these very conventions sentencing them to penury without a way to survive. It has been interesting to place her historically before some of my other beloved authors such as the adult novels of Frances Hodgson Burnett and Edna Ferber (a few of those posts are here and here, but there are others!) but interesting to add her to the timeline. Also, the play between the British authors and the American is interesting as women in the United States seem to have been freer to pursue a living more broadly than their British counterparts earlier on – and the conventions of our society a smidge less confining.

As stated in my earlier posts, Jessie de Horne Vaizey spends the last years of her life bedridden and dies in 1917. I learned recently however that it was first typhoid, then eventually arthritis which confined her to bed and she died unexpectedly during an operation for an appendicitis – so what made her an invalid is not what killed her. She does some of her characters painful rheumatic complaints, usually elderly men, but clearly she knew what she wrote of – and as someone who suffers from it myself, I can only imagine the kind of pain she must have had without the meds of today to help alleviate them. There are also many plot instances of long recoveries from illness, not unlike her typhoid I assume. She was my age when she died, but she made the most of her almost two decades as an author.